- Home

- James Knowlson

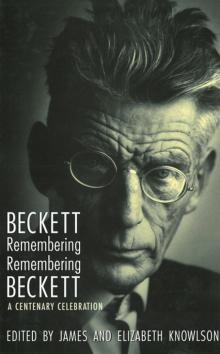

Beckett Remembering / Remembering Beckett Page 10

Beckett Remembering / Remembering Beckett Read online

Page 10

As the children were living in what was the dining-room, we used to eat our meals in the kitchen. So, in order to go to the toilet at the end of the garden, the Becketts had to pass through the kitchen. They did this every day about half past one or two o’clock while we were eating. And my mother said, ‘I’ve never seen anyone so badly brought up in my life. How long are they going to stay here?’ And when Beckett came through, chamber-pot in hand, she used to say to me - in Russian - ‘There is the madman who always comes through when we are eating!’ The Becketts used to go out for walks at that time. It was considered safe enough. And when my husband came out for long weekends, Beckett would go out for long walks with him. My husband got on as well with Beckett as I got on badly. Beckett couldn’t seem to bear that I should have the least literary pretention. Even though at the time he admired enormously Simone de Beauvoir, my own aspirations seemed to annoy him. He had lent us the French translation of Murphy and when the Gestapo came to pick up my husband as a hostage, we had Murphy on the table. They wanted to take it away with them. He said, ‘Why ever do you want that? That is of no interest to you’. But they took it away none the less.

The word ‘grateful’ didn’t seem to be in Beckett’s vocabulary. An old friend of mine, an American woman who knew him well, once said: ‘Oh, he never forgives you for any service you do him. He doesn’t like to be in anybody’s debt.’ You call that pride, do you? I would call it unworthy. As Proust says, ‘un homme très ordinaire peut habiter un génie’ [‘a very ordinary man can inhabit a genius’]. We are not talking of the genius that you can see in his work, but the man that inhabits the genius. And after the war, he came here once when my father was very, very ill. He stayed for only a quarter of an hour, then he left. According to Mania, it seems he was unhappy because my father was not very agreeable to him. Now my father could hardly walk at the time and used to get very impatient and cross as a result.

I empathized very much with Mania. She helped Beckett a lot with his French after the war. She was an agrégée d’anglais, you know, although she spoke English with an incredible Russian accent, whereas she spoke excellent French. Beckett used to send her pneumatiques [i.e. telegrams delivered speedily in the Paris area] to ask her how to say something.*

Escape to the South

‘Nous avons fait les vendanges, tiens, chez un nomme Bonnelly, a Roussillon’ [‘We were picking grapes for a man called Bonnelly, in Roussillon.’] Vladimir in En attendant Godot (Waiting for Godot).

Beckett’s rented house in Roussillon.

Samuel Beckett We tried to get over the line [between the Occupied and the Unoccupied Zones] at Chalons. We just didn’t know where to go. I think we finished up in Toulouse. Then Suzanne remembered friends [Marcel and Yvonne Lob, née De-leutre, and Yvonne’s brother, Roger] she had in a little village in the mountains that was Roussillon [in the Vaucluse]. We went there and lay low. I remember staying in a little hotel [known locally as the Hotel Escoffier, after the name of the owner] before some friends got us a bedroom and a bathroom in an unoccupied house. That was where we met Josette and [the Polish-born painter] Henri Hayden. I used to play chess with Henri. He came to play with me.

Bonnelly was the one with the vineyard. We used to pick grapes for him. I also remember the Audes. Aude had a large family with two daughters. One of them used to cycle up the hill. Their farm was down the road. We used to go and work on the farm. They’d give us food. And once a week we used to go and eat as much as we could, I remember!

I didn’t really get involved in the local Resistance until the last few weeks when the Americans were coming. I remember going out at night and lying in ambush with my gun. No Germans came, so I never had to use it.

I only wrote in the evenings. We used to work during the day. I started writing Watt in the evenings.

[There was] Miss Beamish.* She used to live with an Italian woman called Suzanne Allévy. She [Suzanne] was small, dark-haired. Miss B was the masculine one of the couple. She used to dress more like a man. Do you know where the house is? There are still people there who will remember me. It’s a very different place now. We had a room with a kitchen on the ground floor, I remember. Just outside Roussillon, on the road to Apt, on the corner. Miss Beamish was facing us. She had the whole house, and her girlfriend, and her dogs, her Airedales. Did you know she used to breed Airedale terriers in a kennel in Cannes? She was very likeable. She used to walk out with her dogs; she’d go down to do some shopping in the village. We weren’t far from the centre.

Anna O’Meara (pen-name Noel) de Vic Beamish, Beckett’s neighbour, with her Airedale terriers.

At the end of the war, it was terrible! The forces just opened up the extermination camps as they came through. They had nothing to eat, those of them who were left alive. So there was cannibalism. Alfred [Péron] wouldn’t do it. Amazingly he got as far as Switzerland and then he died of malnutrition and exhaustion. After the war we saw quite bit of Mania, Alfred’s widow. She used to check on the French [of my work], I remember.

Fernand Aude* Samuel used to come to work with us on the farm almost every day. At that time I was seventeen years old and he was forty-odd [in fact Beckett was not quite as old as this: he was thirty-six to thirty-eight during his stay in Roussillon]. He worked regularly on my father’s farm. And he worked for nothing. We wanted to pay him - but he wouldn’t hear of it. I used to say: ‘Stop, Sam, you’re exhausting yourself’. But he would answer, ‘No, no. I’m fine. If I help you, you’ll finish a lot faster’ … He used to eat with us sometimes in the evening. We would eat very late. He would bring in the milk and collect the eggs before supper. Suzanne used to come with him as well and eat with us. It was about five kilometres from Roussillon to Clavaillan. But they used to come on foot, and then they would walk home about eleven or twelve o’clock at night, since we didn’t have room to put them up for the night. Suzanne was very nice; she helped my sister a little in the kitchen, getting the meals and so on. But she didn’t like work too much. Whereas Sam, oh, he would do absolutely anything: climb trees, pick cherries, gather melons, pick grapes. He helped us with harvesting the wheat and with the ploughing; we used to plough between the vines …

Henri Hayden’s pen-and-ink sketch of Roussillon.

Someone else who Sam knew locally, someone he worked for cutting up wood and so on, a farmer, Monsieur X … profited from the black market. He tried to feather his own nest. Samuel did not like that. He was such an honest man, Sam, as straight as a die.

Yvonne Lob* My brother, Roger Deleutre, was a friend of Suzanne’s and it was through him that the Becketts came to Roussillon. As soon as the Nazis arrived in Paris, Roger came to join us here, where we had been settled for some months, living off the land. My husband [Marcel] had lost his university post because he was a Jew. And when Sam had trouble with the Nazis in Paris because he was in the Resistance, my brother wrote to him to let him know that he could come here and we would find some way to put them up.

The problem was that Sam was a foreigner and this made things difficult. However, my husband [Marcel] went to see the Secretary General of the Préfecture in Avignon, whom he knew, saying that he was a friend of my brother and he managed to get permission for him to stay, as long as he did not move from Roussillon. He was, after all, from Ireland, a neutral country, and they knew where he was. But it did mean that he could never leave Roussillon for the whole of the time he was here.

Sam and my husband never really got on together or, more precisely, my husband did not get on with Sam. He was the exact opposite. For me, Sam was a saint with all that the term implies, whereas my husband was a pure rationalist. There were times when I found it quite difficult to keep the peace within the house because there were a lot of us and, as well as the family, we also sheltered refugees from time to time. My husband was never easy-going but losing his post at the university simply because he was of Jewish origin - he was not even a practising Jew at that - embittered him greatly. I understood how he was su

ffering. But he really was very intransigent.

I remember one day Sam was given a piece of beef by the Audes, on whose farm he worked. Meat was, of course, extremely rare in those days of rationing. Sam brought it to me and so I said, ‘If you are giving me meat, then you must come over for dinner this evening.’ So I cooked it. There were a lot of us round the table when, over something too trivial even to remember, Marcel took offence, lost his temper and left the table. On that occasion, I went after him and persuaded him to come back again but that was the kind of thing which happened, preventing our relationship with Sam and Suzanne from being all that it could have been. Despite both of them being intellectuals, Sam and he never really hit it off.

Sam and Suzanne came round quite often and I remember one time saying to Sam, ‘You know, if you fancy reading anything in English I have a lot of English novels.’ ‘That’s an idea’, he replied. There must have been times when he didn’t feel inspired to write and preferred to read and I introduced him to works he didn’t know. I told him to take whatever he wanted and he did. ‘Ah’, he said, ‘That’s not bad’. It was Hugh Walpole. I introduced him to Hugh Walpole whom he had never read before.*

I knew Suzanne first but I got on well with Sam because we had certain things in common. We didn’t speak English together because those around us didn’t speak English. His French was very good but sometimes, when we discussed books, we spoke in English. We got on very well. I found him very human and easy to become friends with.

After the war Sam and Suzanne returned to Paris as soon as they could. I never saw them again except for one time when I went to spend Christmas with Roger and Denise [his wife]. We went to a concert on the Champs-Elysées and in the interval my brother told me that Sam and Suzanne were there with a niece from Ireland [Caroline Beckett] who had come to spend a few days with them. It gave me real pleasure to shake his hand. That was the only time I saw them after they left Roussillon.

I must say one thing. Apart from En attendant Godot, which is accessible, I have never been able to read anything of his. Never. I am probably just too Cartesian. I am open to a lot of English literature, because it was my profession, and when the first volume of Molloy came out I thought I really must buy that. I tried to read it but I simply couldn’t stomach it and gave it away.

The Irish Red Cross Hospital, Saint-Lô*

‘The Capital of Ruins’: the Normandy town of Saint-Lô after the war-time bombing.

Samuel Beckett Saint Lo, ‘The Capital of Ruins’. [After the war, when he had returned to Ireland] I went over with Colonel McKinney and Dr Alan Thompson [brother of his old schoolfriend, Geoffrey] to set things up. We went over in the boat with the first lot of stores. At first they were stacked up on paper. I don’t know where they were being kept but they weren’t ready for shipping. I can remember them all piled up on the quayside; a large amount of stores. Then we were joined by the rest of the group, Dr Arthur Darley, and the surgeon, Freddie McKee, some others, and then Tommy Dunne joined us. He was my assistant storekeeper in Saint-Leo. I remember Tommy Dunne well, a nice fellow; I got on well with him. Eoin O’Brien told me recently that Tommy had died. His widow, whom Eoin had traced, wrote to me and told that they’d had ten happy years together before he died. Then there was Jim [Gaffney], the pathologist. He died in an Aer Lingus crash, you know. It was my job to store the supplies and do the driving. I used to do a lot of driving, drive the ambulances and the truck. It was a big concern. We had about six ambulances plus the trucks. I used to drive up to Dieppe to get supplies and bring back nurses. McKinney was the organizer. He used to drink quite heavily, when he wasn’t in the brothel!

Simone McKee* My future husband, Freddie, said to my parents, ‘I really must bring a friend called Samuel Beckett out to meet you’, and one day he turned up with him. Both he and my parents were musicians - my father was a very good pianist - and we had a piano that had come more or less unscathed through the bombardments so when Sam felt like playing he used to come out to my parents’ home to play. They also used to sing French songs together.

The job he was doing was really not his kind of thing at all. He had to do quite a lot of administration and he was not a methodical, practical person. As far as his driving ambulances goes, he was a terrible driver. He could hardly see; he was so short-sighted. It was dreadful - really terrifying. He never had an accident but his driving was appalling. When he visited us in Ireland after the war he would sometimes pick me up and take me with my baby, Jean-Luc, out to the seaside but I used to be afraid of being in the car with him, especially with the baby.

I found him reserved but not cold. There was a woman called Mrs Barrett, a Frenchwoman who was married to an Irishman and who came to the opening of the hospital in Saint-Lô as a member of the Red Cross. She didn’t speak much English and after I got married and went to live in Ireland she often invited me to her home about six miles to the north-west of Dublin. On one such occasion she invited me along with my sister and Sam Beckett. She was always taking photographs and Sam detested that. After the first few when she suggested, ‘Shall we take another one?’ Sam said, ‘I could always turn my back, just for a change’ … and that was in 1948!

Beckett with Simone McKee and friends in Ireland after the war, c. 1948. Left to right: back row, Samuel Beckett, Madeleine Barrett, Mr Barrett; front row, Yvonne Lefevre (Simone McKee’s sister), Mrs Barrett, Simone McKee.

He often came to see us in Dublin when he came to visit his mother. I remember how he loved lobsters. My husband loved them too and used to get them from some people he knew who sold them at the market in Dublin. My heart would sink when I saw him come in with them because of having to cook them and break them up. I can still see my husband and Sam on the garden steps, cracking lobsters.

When his mother died [in 1950], Sam came to our house and asked Freddie to go with him to choose the coffin. Freddie was a bit taken aback, it was such an unusual request. Sam had all the measurements and so on with him. It was all rather morbid, I felt. It was only after Godot and what followed that I thought back to those outings to the sea with Jean-Luc when there was no thought of his being so intelligent, so learned and so exceptional, when to us he was just the most natural of men.

Beckett in Ireland after the war (almost turning his back), c. 1948.

* The quotation from John Kobler (1910-2000), biographer of Al Capone and John Barrymore, among others, and journalist, is borrowed from ‘The Real Samuel Beckett: A Memoir by John Kobler’, Connoisseur, July 1990, p. 59. Kobler recounted the same story to me [JK] in an interview, but it is better expressed here.

† Beckett visited the Bethlem Royal Hospital much less frequently and over a shorter period of time than this suggests. Thompson left as Registrar in fact after a nine-month-long appointment which was extended for three months more and in any case Beckett returned to Ireland in December 1935.

‡ Duncan Scott’s memories of a conversation with Beckett about his days in London and about Murphy are published for the first time with the agreement of his widow, Bernadette Scott. For information about Duncan Scott, see ‘Memories of Beckett in London and Berlin’, pp. 214ff.

* An allusion to Beckett’s play That Time, although not an actual quotation from it.

† Mrs Ursula Thompson (1911-2001), widow of Dr Geoffrey Thompson (1905-76), the psychoanalyst who helped Beckett to embark on a course of therapy with Wilfred R. Bion at the Tavistock Clinic in London in 1934-5. Interview with JK. We are most grateful to their daughter, Mima Thompson, for her help.

* Beckett toured the wards at the mental hospital in mid-September 1935. This is established by a letter to his friend, Tom MacGreevy, undated but 23 September 1935 (TCD). The tour represents an important moment in the writing of his novel Murphy (1938).

* Beckett’s comment on being chosen as godfather was reported by the Thompsons’ daughter, Mima.

* J. M. Coetzee (1940-). Nobel Prize Winner for Literature 2003. Author of Dusk-lands, In the Heart of the C

ountry, Waiting for the Barbarians, Foe, Age of Iron, The Master of Petersburg, Elizabeth Costello, and Slow Man. Both the Life and Times of Michael K and Disgrace won the Booker Prize. His non-fiction includes: Boyhood: Scenes from Provincial Life and Youth. He wrote his PhD thesis on Samuel Beckett’s novel, Watt.

† Copyright © J. M. Coetzee, 2004. An earlier version of this piece appeared in Passage (Sydney), no. 2, 2003. It was revised by J.M. Coetzee for this volume in 2005.

* The specialist on Sardinia was M. F. M. Meiklejohn, who later became Professor of Italian in the University of Glasgow. He was also a distinguished ornithologist.

* Beckett had known Péron since his student days in Dublin, when Péron had been the French lecteur at Trinity College. They had also worked together in 1930 on the translation of James Joyce’s ‘Anna Livia Plurabelle’ and on the French translation of Beckett’s own novel Murphy. Alfred and Mania, his Russian-born wife, stayed firm friends with Beckett throughout the 1930s. Then he and Alfred were to work closely together as fellow members of the Resistance cell in Paris until Péron’s arrest in August 1942

† Andre Lazaro, the photographer of’Gloria SMH’, also known to the group as ‘Jimmy le Grec’ or ‘Jimmy the Greek’, survived imprisonment in Mauthausen concentration camp and died in Paris in November 1996.

* The informer was a Catholic priest named the Abbé Robert Alesch. See Damned to Fame, pp. 311-18.

Beckett Remembering / Remembering Beckett

Beckett Remembering / Remembering Beckett