- Home

- James Knowlson

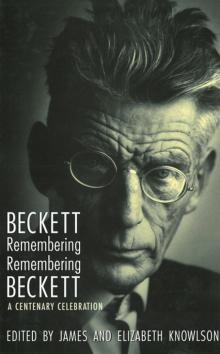

Beckett Remembering / Remembering Beckett Page 15

Beckett Remembering / Remembering Beckett Read online

Page 15

He said that in his work he had been searching for a ‘syntax of weakness’. For form is an obstacle, a ‘sign of strength’. Beckett said that this represents a ‘clash of two incompatible positions. This will come to an end long before life comes to an end.’

‘I don’t know any form that doesn’t shit on being in the most unbearable manner. Excuse my language!’

Restlessness and Movement

[Lawrence E. Harvey asked Beckett further about the sense of le néant (nothingness) in his work.]

Beckett responded that it is more - or at least he moved directly into this related theme - a sense of ‘restlessness, of moving about at night’. Much of this is to be found in my work, he said. There is none the less the sense of having to go on (cf. Comment c’est). Beckett mentioned that Molloy, even when he is really beaten down, feels that he must keep on moving. By contrast, he mentioned a great desire just to lie down and not to move. This is apparently balanced and perhaps even determined by the above restlessness, the opposing compulsion to move on.

When I mentioned the Eden-Exile tension that I found in his work, Beckett objected and described life as being ‘just a series of movements’. He no doubt objected to the meaning that I tried to introduce into what he described as essentially senseless moving about. (Compare the circular motion in Waiting for Godot that gets one nowhere.)

His Life and His Art

Beckett said that in his view his life had nothing to do with his art. He didn’t at least see any relation. But later in speaking of the Irish place names that occur in his poems, Echo’s Bones, he said, ‘Of course, I say my life has nothing to do with my work, but of course it does.’ The word that he used repeatedly was ‘materials’ to be used.

I suggested that I wanted to steer a line between the extreme of art for art (with no relation to life) and autobiographical art (art and life as one). I added that it seemed to me that art could be a reality that was just as real as existence. He seemed to acquiesce with this and replied: ‘Molloy was begun in order to find oxygen to breathe -to make my own miserable existence.’

Later he said ‘Work doesn’t depend on experience; it is not a record of experience. But of course you must use it.’

He feels, he said, ‘like someone on his knees, his head against a wall, more like a cliff, with someone saying “go on”.’ Later, he said, ‘The wall will have to move a little, that’s all’. He also said, ‘It’s not me; it’s my work that has got me into this position.’ I suggested that theatre was still possible for him, because of links between life and the void. He agreed.

‘Children build a snowman. Well, this is like trying to build a dustman.’ I forget how this arose but the point is that it [what he was trying to write] would not stay together. There was his sense of destruction and of the futility of words. And yet at the same time there was the need to make too.

Revolt

Beckett said that there was ‘no revolt at all’ in his work. When pressed, he conceded that there was a little revolt in the early poems but that this was superficial. He used the terms ‘complete submission’ and said that he was ‘revolted but not revolting’. He was using the word in its etymological sense of turning away from but not active opposition to. He sees the individual as having been the subject of a form of destruction and is more passive than active.

Aidan Higgins on Beckett in the 1950s

Aidan Higgins (1927—). Irish writer whose first novel, Langrishe, Go Down, won the James Tait Black Memorial Prize and the Irish Academy of Letters Award. It was later filmed for television with a screenplay by Harold Pinter. Other works include Balcony of Europe (1972), Lions of the Grunewald (1993) and the trilogy, Donkey’s Years (1995), Dog Days (1998) and The Whole Hog (2000). He is also known for his shorter fiction and travel writing. The interview with JK was revised by Aidan Higgins in 2005.

We were living in Greystones, County Wicklow in the late 1940s, and Samuel Beckett’s uncle Gerald and his wife, Peggy, were next-door neighbours. I met their son, John, and he lent me four books, among them Beckett’s Murphy. The others made no impression on me, but Murphy raised the hair on my head. Murphy was the business.

Peggy Beckett said, ‘If you like it as much as that, you must go and see uncle so-and-so in Donnybrook’. This was Walter Beckett, a musician - all the Becketts were musicians. We had a drink or two and he went upstairs and came running down with a brown paper parcel and in it was More Pricks than Kicks, a rare book which you couldn’t get in those days. He said, ‘This is for you,’ and I said ‘I can’t possibly take it off you’. ‘No,’ he said, ‘Sam means something to you which he will never mean to me and you are welcome to it.’ None of the Becketts had any notion what he was up to. If he’d been a musician, they would have understood, but not being serious readers, they had no idea. And then I read Proust in the National Library, which was also unavailable elsewhere. It made a very powerful impression.

I wrote Sam a fan letter about Murphy and John Beckett said it’s no use writing to Sam, he never replies. But he did reply, though it was no use to me because I couldn’t make out the handwriting. The calligraphy was a beast: the hasty hand of a hard-worked doctor firing off prescriptions. Eventually Peggy Beckett, the mother of John, deciphered it as: ‘Despair young and never look back.’ In the same letter he wrote, ‘For wisdom, see Arland Ussher’. So, through Beckett, I met Arland Ussher, and, through Arland Ussher, I met Arthur Power and Joseph Hone. This introduced me in my early twenties to a whole new world.

I remember having tea with the Hones one day and they said what a difficult guest Beckett was. He had come round one evening and Mrs Hone said, ‘Sam, the dogs have pupped’. And Sam said, ‘I’m not interested in dogs’. ‘The cat has …’ ‘I’m not interested in cats’. No matter what subject came up he wasn’t interested in it and he relapsed back into a heavy silence which they were doing their damnedest to break up, and it wasn’t having any effect whatsoever. Anyway, at the door he gave a limp hand to Mrs Hone and said, ‘Friede, Friede’, and she said of course, ‘My name isn’t Freda’, but Ussher happened to be there and said, ‘It’s the German for peace’. So the young Beckett was getting very difficult to entertain and when he said something that was pleasing, they didn’t understand what he was saying.

[It was somewhat different with Arland Ussher, whom Beckett had known in the 1930s.] Ussher was an academic and he had no connection with life as we know it. Sam, although he was very academic in a way, had been, after all, in the Resistance and was very much in life. I remember once Ussher saying to me, ‘You know, I had an evening with Sam and it got very sticky indeed,’ and eventually it relapsed into silence in some bar or other and then he heard that the Sinclairs, the relatives, were upstairs carousing and they went up. ‘And Beckett immediately changed. He became quite different.’ Now something like that would affront Ussher greatly. If he and Sam were together, he thought they should be buddies. If they can’t talk, he wouldn’t like it. But the reason he wouldn’t like it is because Sam lives in two worlds, he lives in the rough, tough world very much and he lives in the abstract world, too, and there he was bored. Sometimes he gets bored with the abstract world and he wants to join the rough stuff.

I first met Beckett some years later in London, during the Criterion Theatre production of Godot [at the beginning of December 1955] which had effectively bowled me over. He was coming down from Godalming with Peter Woodthorpe (Estragon) and a lady who had been at Trinity College with him. John and Vera Beckett were then living on Haverstock Hill, and invited my wife and me over for a supper (silverside of beef, as I recall, done quite rare), to meet Beckett.

The party from Godalming arrived maybe an hour late. I wondered whom I would meet, Democritus or Heraclitus. Well, in the event, neither. It must have been Sunday. The murmurous Dublin accent was lovely to hear; he was not assertive, taller than I had expected, carried himself like an athlete. He had a copy of Texts for Nothing in French on the mantel, stood with me after the mea

l, asked my wife’s name and inscribed this copy.

The following evening we accompanied the Becketts and Michael Morrow to Collins Music Hall in Islington, where the young Chaplin had performed in Fred Karno’s troupe. A nude chorus girl was pushed across the stage on a bicycle, but what affected Sam Beckett was the row in stitches at Mr Dooley, who gave a rapid-patter monologue on what the world needed, which was apparently castor oil. It was in essence Lucky’s outpourings at the Criterion. Beckett was leaning forward, looking along the row. On the way out we ran into Mr Dooley, and introduced him to Beckett, of whom he had never heard; Mr D. was chuffed that Monsieur B. had liked his patter. It was all good clean fun.

The austere playwright, thought to be so reclusive, wasn’t so reclusive after all, as close and enduring friendships with actors and actresses testify; as did the business of conducting much of his social life in bars and cafés. He seemed to be well aware of what was going on in the world at large, lived in no ivory tower.

He himself was not cold and inspired warm affection in others.

‘When you fear for your cyst think of your fistula. And when you tremble for your fistula consider your chancre.’ (Murphy)

Beckett in the Luxembourg Gardens, 1956.

Avigdor Arikha on Beckett and Art

Avigdor Arikha (1929-) is an internationally renowned artist whose paintings, etchings and drawings hang in galleries throughout the world. But he is also a distinguished scholar, having written catalogues for exhibitions which he curated at the Louvre (Poussin) and the Frick Collection (Ingres) and articles for many art journals. He has made documentary films on Velazquez, Poussin, Vermeer, David and Caravaggio and given talks on the radio for the BBC, France-Culture, Deutsche Welle and Kol-Israel. He was a close friend of Samuel Beckett from 1956 until the latter’s death in 1989. Contribution written especially for this volume.

In spite of his great erudition, Beckett refrained from theorizing - even concerning Dante. Unlike erudition, theorizing stops at the white page. His knowledge of lives past telling how it was made them his hidden companions to say how it is -’essayer encore une fois de dire un petit peu ce que c’est que d’avoir été la’ [‘to try yet again to say a little of what it is to have been there’], as he formulated it in a letter.*

He was early on attracted to erudition which sustained his interest in art. This interest started even before Beckett lived at 6 Clare Street, Dublin, next door to the National Gallery of Ireland. Simply looking at paintings without knowing what he was looking at did not satisfy him. He had a passion for scholarly catalogues and acquired them avidly. They accompanied him from painting to painting, in the museums and galleries he frequented, wandering through London, Florence, Hamburg, Munich, Berlin, Kassel, Leipzig, Dresden, Braunschweig, Erfurt, Vienna, Milan, Dijon, to mention but a few.

He sometimes annotated these catalogues by a mark or a note such as the one in the 1928 edition of the NGI [National Gallery of Ireland] catalogue (cat. no 443) next to the entry concerning Hendrick Gerritsz Pot, Portrait of a Man. Beckett inscribed in the margin ‘at same time as Ter Porch’, and underlined in the entry the line England 1632 (the year Pot painted the portrait of Charles I, now in the Louvre). While living at 34 Gertrude Street, London, SW10 [1934-5], Beckett inscribed, on one of his visits to the National Gallery, the NG [of London] catalogue (edition 1929), near the mention ‘Butinone see Milanese School no 2513,’ printed without surname or referred work: ‘Adoration of the Shepherds: given to Mantegna, then to Parenzo’ and added in the margin no 3336. Beckett’s attribution was right. It is not a Mantegna, nor a Parenzo, and was ascribed, by Martin Davies (1956) to Bernardino Butinone under no 3336. He sometimes marked an analogy, such as the one inscribed in the catalogue of the Staatliche Gemäldegalerie zu Dresden, on the margin of no 958 (cat. 1930), entry Rubens’ Old Woman with Ember, c.1616-1618:’Honthorst’. Or emphasizing a particular detail of the work seen, such as the note on the margin of the entry to Caravaggio’s Christ on the Mount of Olives in the Kaiser Friedrich-Museum, Berlin: ‘Peter’s foot.’

It is amazing that his qualitative discernment was there from the start, not simply looking for celebrated works but for pictorial qualities. His discernment sharpened along with the widening of his visual culture that spanned past and present. He was aware that the visual experience differs from the literary one. ‘Art and literature can’t mix, they are like oil and water’ he said, adding ‘I don’t know which is which’.

His visual sense was as intense as his musical one. In later years he often sat gazing at a painting, print or drawing a long while without uttering a word. He would simply gaze, marvel, nod, and sigh.

Martin Esslin on Beckett the Man

Martin Esslin (1918-2002). Writer and radio producer. He was appointed the Head of the Radio Drama Department at the British Broadcasting Corporation in 1963. Author of many books, including: Brecht (1959), The Theatre of the Absurd (1961), Brief Chronicles: Essays on Modern Theatre (1970) and Pinter: A Study of his Plays (1977; first published in 1970). Interview with JK.

I was trying to write a book about the theatre of the absurd in 1960 and felt I wanted to interview the writers concerned. Through Cecilia Reeves, who was the BBC representative in Paris and who knew Beckett, I managed to get an interview with him in the rue des Favorites at the beginning of 1961.

I had, of course, looked up all the cuttings about him beforehand so that I was well prepared. But there was very little in the BBC cuttings library, except for a long Observer profile, which contained some rather sarcastic references to his being very much under the sway of his mother and all sorts of things and the suggestion was that he might well be homosexual.

He was there all by himself. He said, ‘How very nice to meet you. You can ask me anything about my life but don’t ask me to explain my work’. We got on like a house on fire. He gave me a copy of Echo’s Bones with an inscription. It was a numbered edition, i48. Then he told me all about going to Germany before the war and wandering through Europe and how it left him feeling. And [we talked about] Trinity College, Dublin and so on. And all this time I was wondering whether I could ask him about women, about whether he was married.

He opened a bottle of whiskey and I thought my goodness, what a wonderful man. The most attractive man I’d ever met, in a way, and what a nice friendship was developing here. Then I thought, my God, can I ask him ‘Are you married?’ or ‘What about women?’ He was so scathing about this article in The Observer that I thought he would get furious and throw me out. And so I was in this Racinian conflict of conscience, between my duty as a researcher and my duty as a potential friend. In the end my friendship won and I didn’t ask him.

He said, ‘Well, send me what you have written. I can see whether there is anything I can help with.’ And I was very happy but when I walked down the street, I said to myself, ‘My God, now I’ve done it.’ I already saw the review in The Times Literary Supplement: there is this snotty-nosed urchin from Vienna who pretends to be a biographer and he doesn’t even know whether his subject is married or not! The same evening I went to the theatre with a friend of mine. It was very late; we were having dinner after the theatre in a little Chinese restaurant in the rue François Premier and we came out about 2 o’clock at night. It was a wonderful spring evening. The Champs-Elysées was completely deserted, when, suddenly from the other side, I heard a voice saying, ‘Mr Esslin, meet my wife,’ and there was Beckett with Suzanne. This stumpy little woman was then introduced. And I said to myself: ‘My God, virtue has been rewarded’. Anyhow, so I met her. Then I went back to London and wrote my piece.

The chapter on Beckett for The Theatre of the Absurd was about forty or fifty pages long. I sent it to him and it came back with little red corrections of some of the biographical details, together with a letter which said, ‘I like this because you raise many hares without pursuing them too far’. So that meant that he gave me his blessing and that was very encouraging for me. Just at the beginning of 1961,

I had got the job as Assistant Head of the Radio Drama Department of the BBC, and this of course meant that I was the successor to Donald McWhinnie. Val Gielgud, who was the head of the department, took me out to lunch and he said to me, ‘I hate Brecht, I hate Beckett, I hate Pinter. But I know what my duty is. That’s why I’ve appointed you to deal with those people’. At that time John Morris was still the Controller of the Third Programme and he had been instrumental in getting Beckett to do All That Fall and Embers, but also the first readings from Molloy and Malone Dies by Jackie MacGowran and Pat [Magee]; Froman Abandoned Work also. And so, because Val didn’t want to have anything to do with this, it fell to me.

Beckett at Greystones, 1960s.

The connection between the BBC and Beckett was that Donald McWhinnie was detailed to do the directing of All That Fall and he went to Paris and saw Sam about it and Sam immediately took to him. He really fell in love with him, and vice versa. They became the best of friends and that of course established a connection that went on and on. In a way I inherited that because I was the successor to Donald and fate luckily had meant it that I’d just met Beckett and he’d seen what I’d written about him. So he took to me in the same way, although perhaps not so passionately, as to Donald McWhinnie.

Beckett worked very much that way, with friendships. He wanted people whom he could trust and with whom he could work. So the next thing that happened was that there was some sort of jubilee, the fiftieth anniversary of the BBC or something like that, and we were told, again by the Third Programme, that we ought to have something by some big name, a world première, so that we’d get into the papers to celebrate this anniversary. So I wrote to Beckett and said, ‘This again is a possibility, would you like to do something?’ And he wrote back saying ‘Not really, I don’t work like that’. But then, I think he actually came into the office and said, ‘By the way, my cousin John is in such a bad way [for he had had a horrific motor accident], I have had an idea which would give him some work.’ So that is how Words and Music came about and he wrote something where the music was of equal importance to the words. I remember even when we were doing Words and Music, I went to the editing channel, he was in the editing channel and he said, ‘No that six seconds should only be five’. He was very, very meticulous, very precise.

Beckett Remembering / Remembering Beckett

Beckett Remembering / Remembering Beckett